Clergy sexual abuse

Going deep into the Vatican files, this week’s installment looks at the apostolic administrator as a proxy of the clergy sexual abuse crisis.

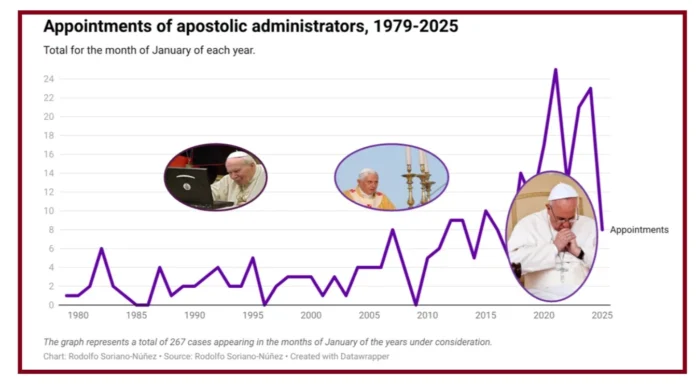

The boom in the appointments of apostolic administrators, 1979-2025. John Paul II’s picture by H. Michael Karshis, and those of Benedict XVI and Francis by Mazur/catholicnews.org.uk.

Even with a limited sample, the data shows an explosion in the number of clerics appointed as apostolic administrators.

The sample looks only at the appointments of apostolic administrators made during the months of January from 1979 through 2025.

To understand what is behind the Vatican’s response to the clergy sexual abuse over the last 40 years or so, this series has been using different approaches to explain what is happening and, perhaps more significantly what could happen in the future if trends and patterns remain as they are so far.

That is why, after looking at how intense is the demand for new appointments of bishops and how able are the seminaries to shape future generations of prelates in samples of 46 countries, representative of roughly 80 percent of the global Catholic flock, this weeks’ installment looks at a key piece of evidence of the scale of the crisis in the Catholic Church.

Even if there are places where the Church seems to be in denial mode, it would be naïve to assume that nothing has changed since the days when Jason Berry broke the equivalent of the Catholic Church’s Watergate in the 1980s.

If back then the hierarchy was barely willing to admit some cases in the United States, Berry offered the first account of what nowadays is an all-too-common story: moving religious leaders from one location where they have caused troubles to another. Over the last three years or so, this series has identified that pattern as a “geographic solution,” and has offered specific examples of how said solution has been deployed.

Whenever possible Catholic, Anglican, Orthodox, Lutheran, and Mormon bishops, as much as leaders of other Christian denominations and other religious organizations use that short-term “solution” to mask a systemic issue. These maneuvers echo what happens around the Epstein files and their ripple effects in the United States, the United Kingdom, and other countries, as much as with other sexual predator cases in other settings..

When that “solution” is no longer useful, whether because of social mobilization uncovering the transfers, or when the documented cases are as many as they were in Boston, Los Angeles, Santiago de Chile or in orders such as the Legion of Christ, there is the need for some kind of intervention.

During his meetings with cardinals at the consistory held on January 7-8, Leo XIV acknowledged the gravity of the abuse crisis. In his final message, he urged the cardinals to prioritize victims’ reports and complaints. His message, only available in Italian here, is partially translated into English in this Vatican News story about the consistory.

Intervention, Vatican style

The interventions in Catholic settings are basically three. One is the so-called apostolic visitation. The second is the appointment of a coadjutor bishop, and the third, is the appointment of an apostolic administrator. While the visitation can be applied to dioceses, orders, and other entities in the Catholic Church, appointments of a coadjutor or an apostolic administrator are only for dioceses.

It could be that a visitation leads to any of the two other possible interventions, but there are cases where a coadjutor or an administrator is appointed without a visitation.

The visitation happens when a diocese or order is asked to receive a Vatican envoy who will gather information to offer some sort of report to Rome. A few weeks ago, the series offered details of how that solution has been administered to the Emmanuel Community, a highly influential religious movement in the French-speaking world, linked after this paragraph.

The Legion of Christ was subject to a similar measure during Benedict XVI’s tenure. An example of dioceses that have gone through it, is Ciudad del Este, Paraguay, in July 2014, as the story linked above proves in the section titled “Memories of other visitations.”

Another form of intervention is the appointment of a coadjutor bishop. Usually, it is a sign that there is grave financial mismanagement, sexual abuse and in some cases, they also happen as a response to other reasons in any given diocese.

The most notable of such appointments of a coadjutor for other reasons happened in Mexico in August 1995, when John Paul II sent Raúl Vera López to San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, 17 months after the uprising of the Zapatista National Liberation Army against the Mexican government in January 1994.

It would be impossible to dig the memories of that appointment at this point. Suffice to say that media closer to the Mexican government saw it as some sort of criticism of Samuel Ruiz. Vera López avoided the usual dance between the sitting bishop and the coadjutor, so no trouble came out of it, but that is not the usual outcome.

Three decades later, Leo XIV appointed a coadjutor in Santo Domingo, capital of the Dominican Republic. It is unclear what is behind the appointment, but there is no military conflict as in Mexico in 1995.

Francisco Ozoria Acosta the current archbishop was forced to welcome, at 74, Carlos Tomás Morel Diplán as a coadjutor who, as a sign of the times, remains the apostolic administrator of his previous diocese, that of La Vega.

Morel Diplán’s appointment is harder to grasp, as Ozoria Acosta has less than one year before resigning. It is harder to understand why Morel Diplán went from celebrating Ozoria Acosta’s appointment to decry it and rendering himself a victim of Rome.

The case proves how contentious is the management of key dioceses all over the Catholic world, a proxy of the kind of pressure in the system. So much that Rome preferred to run the risk of Ozoria Acosta having a public tantrum instead of simply waiting until he reached 75 on October 10, 2026. What is clear is that Rome had some interest in rushing an intervention, revealing some distrust.

Appointments of coadjutors are less frequent as they imply having two bishops in some sort of entente with one retaining the title and honors, while the other takes over, partially or totally, the diocese’s control.

The third type of intervention is that of the appointment of an apostolic administrator. They happened usually after the resignation or death of a bishop, and whenever Rome decides that it is better to avoid rushing the appointment of a new bishop.

Why apostolic administrators?

Today’s installment looks at how the Catholic Church has used over the last 46 years or so, appointments of apostolic administrators as a tool to contain the crisis while promoting certain notions of reform and change.

Wearing a blue facemask and a white shirt, Cardinal Baltazar Enrique Porras Cardozo presides over a meeting of the pastoral teams at the archdiocese of Mérida, January 5, 2021. At the time, he was in charge of Mérida and Caracas. Social media of the archdiocese of Caracas, Venezuela.

Not that the apostolic administrator is always associated with the clergy sexual abuse crisis. Quite the opposite, in cases where the Church-State relation has been strained, appointing an administrator could be the only way to avoid deepening the conflict, as the last story published in 2025 proved when dealing with Jorge Liberato Urosa Savino’s resignation as archbishop of Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, and the troubled appointment of Baltazar Enrique Porras Cardozo, first as apostolic administrator, available after this paragraph.

One sees similar issues when dealing with appointments in Ukraine over the last five years or so or, for other reasons, when one sees at Nicaragua and the ongoing Church-State conflict there.

Despite those realities, noticeable also in places such as Hong Kong or in some countries in the Middle East, the fact is that there are reasons to believe that many of the most recent appointments of apostolic administrators can only be explained as Rome’s attempt to enforce its authority after a scandal has happened or could potentially happen. One only needs to look at sees such as Cádiz Spain; Verdun, France, Juli, Peru, and Tijuana, Mexico.

All of them are currently under the authority of an administrator. In Tijuana, the appointment was the consequence of the sudden death of Francisco Moreno Barrón, but issues associated to the clergy sexual abuse crisis there have been documented for many years now, as the story linked before this paragraph proved.

On top of that, a priest formerly associated to that archdiocese decided to join forces with the schismatic Society of Saint Pius V, a splinter, more radical, organization separated from the Society of Saint Pius X, the one founded by Marcel Lefebvre, who challenged John Paul II’s authority by consecrating four bishops associated to that “order” without Rome’s authorization, and one more from a similar group in Brazil.

The issue would be irrelevant if that priest, Isidro Puente Ochoa, had not been authorized, a few years ago, by the archdiocese to have a seminary under his control where he insists on recruiting underage males as seminarians despite the evidence of the increased chance of sexual abuse in that kind of context, as the Post-Data section of the story linked before this paragraph tells..

Cádiz grabbed headlines all over the world as bishop Zornoza Boy became the first sitting bishop in Spain whose alleged abuse of an underage seminarian of the diocese of Getafe, near Madrid, the capital of Spain, has been probed and acknowledged by the conference of Catholic bishops in that country, as the story linked after this paragraph proves.

In Juli, Peru and Verdun, France, as a testament to the way the clergy sexual abuse crisis has evolved, the now former bishops in both sees were forced to resign their positions.

Ciro Quispe López became a scandal in Peru when news about his promiscuity seized national media, detailing his relationships with at least ten females of his former diocese of Juli, Peru.

In France, Jean-Paul Gusching of Verdun, had his share of scandal after the nunciature to France and French colleagues, admitted he was forced out after he was “caught” in an informal relation with an adult female and, far from accepting his “penalty” he challenged it, as the story linked after this paragraph tells.

The available data

To try to understand why Rome is choosing to appoint apostolic administrators instead of bishops, this week’s piece goes after more data to explain what is happening.

It would be impossible to gather all the data required to carry a full analysis of more than 40 years of appointments in the Catholic Church as to identify when Rome appointed an apostolic administrator instead of filling a vacancy in the global episcopate, whether because of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, to address issues of discipline or to avoid potential conflicts with countries such as Venezuela, Nicaragua, or China.

In that respect, the analysis is based on a non-probabilistic sample of all apostolic administrator appointments recorded in January from 1979 to 2025, as published on Catholic-Hierarchy.org. The sample is chosen for feasibility and consistency as to facilitate a comparison over several decades and pontificates, acknowledging the limitations of manual data extraction and site architecture.

The data is available through Catholic-Hierarchy.org, but access to it is limited because of the website’s architecture and search engine, as it does not allow for the use of complex (Boolean) searches to filter the available information.

As it is, the site allows for the search of some data, but the classification has to be carried manually. It would be unethical to “raid” that site’s information and it could put the author of these lines at risk of being banned, through my ISP identifier, from ever having access to the wealth of data there. Even the use of Excel’s PowerQuery or similar tools is insufficient as it would provide only some of the data, with plenty of manual labor and analysis still required.

Other sources such as the Annuario Pontificio, the Acta Apostolica Sedis or even the daily Bollettino published by the Communications Office of the Holy See would be unmanageable for a team of one trying to figure out what is really happening in an extremely complex institution that, as any other institution, keeps processes secret to address its own issues. As far as the Bollettino, its English- and Spanish-language editions are only available starting in 2016, and the Italian-language edition only goes back to 2000, so, it would be impossible to go beyond that “wall”.

On top of the technical difficulties to build a more reliable database, there is the issue that the Pontifical Secret behind the appointments of bishop and more so behind the decision to appoint an apostolic administrators turn the whole process into the proverbial “black box” of policy studies.

Black boxes allow one to know some of the inputs and outputs, but one is never fully aware of how inputs go through the box as to offer the outputs regarding any given diocese after the death, resignation, forced or voluntary of a bishop.

That is why, as much as it would be better to have a full set of data with all the information about the appointment of apostolic administrators over the last 50 years, it is impossible to do it at this time.

Instead, the exercise has been built on a non-probabilistic sample of all the appointments of apostolic administrators during the months of January from 1979 (the first full year of John Paul II as Pontiff) through 2025 with some very limited spill-over to January of 2026.

Even with that severe restriction, the data set reveals a pattern worth of consideration, allowing to perform preliminary analysis. By looking at the snapshot one gets at the “Events” pages for each month of January at Catholic Hierarchy it is possible to develop a primer of a forensic mapping of its visible friction points that are noticeable when Rome appoints an apostolic administrator.

Anyone can replicate the source for the data by clicking, for example, this page, where the events for the month of January of 2011 appear.

It is a task similar to previous attempts at figuring out how Rome addresses or not the effects of the clergy sexual abuse crisis. First, back in 2023, this series published the story linked after identifying the first one-hundred bishops of whom there is reason to believe were forced out of office by the sitting Pontiff.

The elusive data on apostolic administrators

Even before the start of the clergy sexual abuse crisis appointing an administrator was a way to manage a crisis. The difference is that before 1998, such an appointment was an extreme measure reserved, for the most part, to deal with China and some countries of what used to be, in the context of the Cold War, the so-called Soviet satellites in Eastern Europe and other regions around the world.

The reference to 1998 has nothing to do with geopolitics, and all with the clergy sexual abuse crisis. That was the year when the crises in Palm Beach, Florida, exploded. Palm Beach is different from other episodes of the crisis because it was there where, not one, but two bishops were forced out of office, one after the other, after acknowledging their role in sexually abusing underage males.

First it was Joseph Keith Symons whose chaotic tenure as bishop there force him to resign on June 2, 1998, when he was barely 65, ten years before the age of retirement, after accepting he had molested at least one former altar boy. Symons holds the “honor” of being the first bishop to resign over accusations of clergy sexual abuse.

The “first responder” there was now bishop emeritus of Saint Petersburg, Robert Nugent Lynch who acted as administrator from June 2, 1998, until January 14, 1999. That year, John Paul II appointed Anthony Joseph O’Connell as bishop.

Soon after, as his predecessor, O’Connell was forced out of office at 63, when details about abuse of at least five underage seminarians in Jefferson City, Missouri, emerged. The scandal forced that diocese to acknowledge they have had reports about O’Connell’s behavior at least since the 1960s, when he was a priest.

As a response, John Paul II appointed as bishop of Palm Beach the now Cardinal Sean O’Malley who, before dealing with the mess there, “cleaned” the diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts, where priest James Porter abused at least 28 underage males. O’Malley would be later appointed by Pope Francis as president of Tutela Minorum, the entity set to prevent clergy sexual abuse in the Catholic Church.

Cardinal Seán Patrick O’Malley, O.F.M. Cap., the ultimate firefighter in the global clergy sexual abuse crisis while preaching during a Mass in his former Cathedral, August 31, 2016. From the social media of the archdiocese of Boston.

O’Malley tenure in Palm Beach would be short, as he was called back to New England to deal in 2003 with the larger scandal in Boston. O’Malley, who later would become head of Tutela Minorum, the entity created by Pope Francis to prevent clergy sexual abuse, had to deal there with the pervasive effects of decades of systematic cover up of dozens of cases of clergy sexual abuse as depicted the movie Spotlight, dramatizing the quest of a group of journalists at The Boston Globe to uncover the truth.

Palm Beach had from 1998 through 2003 five different leaders, whether as bishops (Symons, O’Connell, O’Malley, and Gerald Michael Barbarito, the now emeritus who retired on December 19, 2025), besides Lynch who only was apostolic administrator.

Palm Beach is key to understand the evolution of the clergy sexual abuse crisis because before what happened there, the Catholic hierarchy, whether in Rome or in the United States was able to render the issue as one of “bad apples”, as with Gilbert Gauthe in Louisiana.

Palm Beach proved that the “vetted bishops” were also dangerous predators and that they were part of the problem. Indirectly, the five years of hell in Palm Beach, coupled with the revelations from Boston and other dioceses in the United States, forced the Church to acknowledge that its vetting process itself was broken.

After Palm Beach it is possible to see how Rome went from a rather infrequent use of the apostolic administrator, to appointing more and more bishops as such. Although the figure has existed for quite some time, it was Benedict XVI who started using it as a way to address conflict in specific dioceses.

First, he did so as Joseph Ratzinger, when as head of the then Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, he promoted the centralization of such cases under the aegis of that entity of the Roman curia that would be formalized in 2001, as the section “True reach” of the story linked above explains.

Pope Francis used the tool much more than any of his predecessors, perhaps because he was already facing more pressure. A perfect example of apostolic administrators as a tool to manage a crisis, comes straight from the current Pope’s biography.

It is known by now that when Pope Francis recruited Robert Prevost, the then former superior of the Augustine order to become the administrator of Chiclayo, Peru, the Argentine pontiff was already dealing with a crisis there.

Chiclayo had been managed by bishops closely aligned with the Spanish-born Opus Dei, an order of sorts, known for its clericalist and sectarian approaches.

When Prevost first caught Francis’s attention, the Argentine Pontiff appointed him as the apostolic administrator of Chiclayo for ten months: November 3, 2014, through September 25, 2015.

Previous installments of this series, as the story linked after this paragraph, offered details of what was the situation at Chiclayo when Francis appointed Prevost as apostolic administrator.

However, with the available evidence at hand, it is possible to say that even if he was willing to appoint newly consecrated bishops such as Prevost as administrators, the Argentine Pope would rather go with veteran clergymen, archbishops, many of the over 75, to deactivate potential scandals in dioceses with, it is possible to assume, large number of cases.

After taking over Chiclayo, Francis asked Prevost to deal with a second diocese as administrator. That was the case of Callao, a jurisdiction in the Metropolitan Area of Lima, the Peruvian capital, 410 miles or 660 kilometers South of Chiclayo.

That appointment was relevant also because it forced Prevost to confront the leaders of the Sodalitium of Christian Life, and more specifically the bishops in Peru willing to go to war for that now suppressed organization.

Prevost got the “cleaners’” job at Callao after Spaniard national José Luis del Palacio y Pérez-Medel was forced out of office when he was 70. As it is still the standard operating procedure of the Catholic Church, there was little or no information as to why, in the early days of the pandemic, April 15, 2020, bishop Del Palacio’s early resignation was accepted in Rome.

What is clear, instead, is that when he played victim in the Catholic media of Spain, he claimed he was unaware of the reasons why he resigned to the position, as can be confirmed at the page with his data at Catholic Hierarchy, where his exit is registered as a resignation.

Pope Francis receives a religious icon from then-bishop of Callao, José Luis del Palacio, during his Ad Limina visit to Rome, May 2017. From the diocese of Callao social media.

A story published by Vida Nueva Digital also hints at Del Palacio’s membership with the so-called Neo-Catechumenal Way (content in Spanish), an organization with the Catholic Church with close ties with the Sodalitium in Peru and with other predatory Catholic organizations.

The Neo-Catechumenal Way played a major role in the clergy sexual abuse crisis in the U.S. Pacific territory of Guam. The now emeritus archbishop of Agaña, Guam’s capital, Anthony Sablan Apuron was removed from office back in 2019 when it was clear that he was aware of the abuse happening in that see. His close relation with the Neo-Catechumenal Way was a source of pride for him, as this document at the Holy See website from 2008 proves.

The data

Putting these issues aside, what the partial data on apostolic administrators reveals is a clear trend starting with Benedict XVI and increased during Pope Francis’s tenure to appoint administrators in dioceses where, to put it succinctly, given the opacity of the available information “there are issues”.

After going over the 46 months of January (1979-2025) and with records of 267 appointments from such snapshots it is possible to say that Prevost was one of many bishops who Francis appointed administrators to deal with difficult situations in certain dioceses.

In the non-probabilistic sample, the first peak of the post-Palm Beach use of the apostolic administrator comes in 2007, with a total of eight. Just before Benedict XVI decided to resign the office of Pope in 2013, it is possible to find a new peak in 2012 and 2013 with nine appointments of administrators.

Two years into Francis’s tenure, in 2015, a new record of ten appointments happens. In 2018, the year of Pope Francis’s «Chilean Waterloo,» a new record of 14 appointments is set, and in 2021, two years after Francis issued Vos Estis Lux Mundi, the new peak was 25.

It is possible, then, to think of at least three major periods to understand the evolution of the use of the apostolic administrator.

A pre-Palm Beach, where the use of the apostolic administrator was spare and centered around extreme geopolitical issues such as the conflictive relations between the Holy See and the People’s Republic of China, spanning from 1979 through the end of 1997.

Then, a post-Palm Beach/pre-Vos Estis Lux Mundi period ranging from 1998 through 2018, where the current use of the apostolic administrator took form, and finally a post-Vos Estis Lux Mundi period, starting in 2019, the year Pope Francis issued that document, with no visible end in sight.

And the issue is not only the number of administrators used to deal with dioceses with issues. It is necessary to also pay attention to how long some of these appointments are.

Among the most notable, about to end this January, is Rogelio Cabrera López’s, the archbishop of Monterrey, who is still, for a few more days, the apostolic administrator of Nuevo Laredo.

It is unclear why Cabrera López has been for 26 months the administrator of that diocese, as he was before, from March to November 2021, the administrator of Ciudad Victoria, the capital of the state of Tamaulipas, neighbor to the South of Texas, and from July 2018 to July 2019 also administrator of the largest metro in that Mexican state: Tampico.

Even if this pattern has been absent for the most part in the dioceses following the Latin rite in the United States, there are traces of it in some of eparchies, the equivalent of the dioceses for the rites of the so-called Oriental Churches.

Archbishop Rogelio Cabrera López celebrates his birthday at the Monterrey seminary refectory, January 24, 2015. From the social media of the archdiocese of Monterrey.

Much like archbishop Cabrera López in Monterrey, the Ruthenian bishop of Passaic, New Jersey, Kurt Richard Burnette, has been apostolic administrator of three eparchies, two in the United States and one in Canada, the Apostolic Exarchate of Saints Cyril and Methodius of Toronto.

Back in 2018, Pope Francis appointed there Marián Andrej Pacák, a member of the congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer, a religious order, who at 45 was, for a while the youngest Catholic bishop. As it is usually the case in Catholic media all over the world he was praised for his appointment.

Sadly, as it is also frequent, the praise turned into sour doubts when little more that two years after his consecration, he resigned the position and went into some sort of exile to a religious community in his ancestral homeland of Slovakia, with no transparency or accountability as to the reasons for his sudden resignation.

Wonder boys

Marián Andrej Pacák’s case in Toronto, Canada, is a cautionary tale about the risks of appointing young bishops for the sake of youth. It reminds how untested “new blood» is not always the answer.

It also proves that even the Oriental Catholic eparchies, are not immune to the secrecy with which the Latin rite dioceses manage these issues. It also proves how thin is the bench, the farm system, and perhaps validates the caution with which Francis used the apostolic administrator tool to avoid more embarrassing mistakes.

And one could assume that the issue is how foreign the realities of North America and Slovakia were to Francis and his team in Rome, but the fact is that if one goes over some of his appointments in his native Argentina, a territory he knew with greater detail than any other country in the world, there were terrible mistakes.

One notable is that of bishop Gustavo Óscar Zanchetta. A few months ago, Los Ángeles Press published an interview with a survivor of what happened in the Argentine diocese of Orán. Matías testimony about what happened there, available in the story linked after this paragraph, is ever more painful when one considers how Pope Francis tried to minimize what happened there.

As Pacák, Zanchetta was hailed at his time as the promise of the “Francis’s bishops,” new blood for the new agenda the former archbishop of Buenos Aires was trying to bring to Rome.

Francis appointed Zanchetta on July 23, 2013, six months after his own election as Pontiff, when Zanchetta was 49, and as Pacák was, the Catholic media, at least that loyal to Francis, hailed him as the promise of a new bench.

Sadly, little less than four years after his appointment, Zanchetta resigned. As usual, there was no explanation of the move and, to make matters worse, Francis brought Zanchetta to Rome, appointing him as official of what is now the Administration of the Patrimony of the Apostolic See, one of the entities charged with the management of whatever are the earthly possessions of the Holy See.

As the aforementioned interview with Matías, the Argentine survivor proves, the trip to Rome shielded Zanchetta from any meaningful accountability. Despite that, he was found guilty by a court of law in Argentina, but his sentence has been turned into a retirement as mysterious as Pacák is.

And it was not the rural, Northern diocese of Orán, but something similar happened in the archdiocese of La Plata, capital of the province of Buenos Aires, the most populous in Argentina that, for five years (2018-23) was under the aegis of the current prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, Víctor Manuel Fernández. When Fernández got his own ticket to Rome, Pope Francis appointed Gabriel Antonio Mestre.

As Zanchetta, when Mestre was consecrated as bishop in 2017, he was hailed as a “Francis bishop,” and even if against him there is no evidence of accusations of clergy sexual abuse or embezzlement of diocesan funds, less than one year after his promotion from the diocese of Mar del Plata, to the archdiocese of La Plata, he decided to resign, five months shy of 56, and now he is a parish priest.

Then-archbishop Gabriel Mestre at Melchor Romero prison, March 21, 2024, just two months before his resignation at age 55. Social media of the archdiocese of La Plata.

In that respect, what should be clear by now is that the hollow bench described in quantitative terms last week is a painful reality despite the enthusiasm brought to Argentina and Latin America by Francis’s pontificate.

Pacák. Zanchetta, Mestre, and other former “wonder boys” from other decades hardly meet the expectations raised by their appointments. Besides the bishops appointed by Francis in this category, Benedict XVI had his own, as in the case of the former auxiliary of Culiacán, Mexico, Emigdio Duarte Figueroa, who became bishop when he was five months shy of 39 in 2008. Duarte Figueroa was, again, the “youngest bishop” worldwide and the kind of bishop embodying the values and ideals promoted by Pope Ratzinger.

Oddly enough, barely two years later, in September 2010, local media in Mexico “informed” of Duarte Figueroa’s decision to resign his position as auxiliary bishop and “go to the Holy Land” to study.

Only the difficulties brought by the pandemic allowed Duarte Figueroa to resurface, not in Mexico, but in Tegucigalpa, Honduras; no longer showered by the treatment of a bishop, but identified, oddly enough as “Reverend Father,” a title usually reserved to priests affiliated to religious orders, despite the fact there is no data about him ever being a member of an order.

Duarte’s case illustrates that when the Vatican tries to bypass the «hollow bench» by appointing someone young and untested, it often ends in a forced, non-transparent resignation. This reinforces the risk of falling again for John Paul II’s trap when promoting Marcial Maciel and others similar to the Legion’s founder: supporting, regardless of consequence, whoever is willing to pretend is up for the task, following the “fake it until you make it” mantra.

The pattern holds even for those who reached the highest ranks: Bernard Law and Norberto Rivera Carrera were both fast-tracked at 42 and 43, respectively. Their subsequent careers as cardinals only prove that a «wonder boy» promotion is no vaccine against systemic failure; it simply raises the stakes of the inevitable intervention and/or the ensuing scandal.

Africa too

Other notable cases emerging in the snapshots from the month of January of the last 46 years offer similar cases to those of Rogelio Cabrera López and Kurt Richard Burnette.

On the one hand, there is the case of South African Cardinal Wilfrid Fox Napier who has been appointed by two different pontiffs as administrator of dioceses in his home country. On the one hand there is John Paul II’s 1994 decision to send him to Umzimkulu, South Africa. He remained administrator there for 15 years, until Benedict XVI relieved him in 2009 from that duty.

Pope Francis greets Cardinal Wilfrid Fox Napier in Rome. Picture published in 2018 by the Catholic archdiocese of Durban on its Facebook account.

However, at 79, Pope Francis appointed Napier, in 2021, as administrator of Eshowe, and he remains there up until now. In the meantime, a bit later that year, the Argentine Pontiff also appointed Napier as administrator of Durban, his own archdiocese, until Rome found a successor for that see three months later.

A similar case comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo, with the current archbishop of Kinshasa, Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo Besungu, who, before his current assignment, when he was bishop of Bishop of Bokungu-Ikela, and Pope Benedict XVI appointed him, in October 2008, administrator of Kole. His tenure there extended over seven years, as it was Pope Bergoglio who relieved him in August 2015 from that assignment.

He did so only to put more territory under his care as administrator. First, in March 2016, he got the position at the archdiocese of Mbandaka-Bikoro, and eight months after, in November, he became the archbishop while being appointed administrator of Bokungu-Ikela, where he would remain for a year and a half.

Besungu had a very busy 2018. That year he was appointed coadjutor of Kinshasa, while becoming administrator of his former archdiocese of Mbandaka-Bikoro. Since he was already probably working overtime, Pope Francis ended his tenure as administrator of Bokungu-Ikela and, by the end of that year, in November, he assumed as archbishop of Kinshasa on his own, but he remained administrator of Mbandaka-Bikoro until January 2020.

Both Cardinals Napier and Besungu show how the apostolic administrator role has transitioned from a mid-career management tool to an emergency measure. When John Paul II first sent Napier to Umzimkulu in 1994, it followed the logic of using a mid-career bishop to bridge a local gap.

However, his reappointment in 2021 as administrator of Eshowe at 79 illustrates the reliance on the “recalled emeritus” or recycled elite model. This specific case grounds the finding that emeritus participation is a key structural response to a thin farm system; the Vatican would rather recall an 80-year-old veteran than risk an unvetted newcomer from the local clergy.

Napier’s second tour as a “firefighter” is not an anecdote but a data point in the 28 recorded instances where Rome has reached back into the retirement pool to maintain institutional control.

Similarly, Cardinal Besungu in the Democratic Republic of Congo is a similar case of a member of the clergy elite used to address trouble. Besungu’s workload peaked in 2018 when he was simultaneously managing the needs of the dioceses of Kinshasa, Mbandaka-Bikoro, and Bokungu-Ikela, on top of his Roman duties.

This level of consolidation in one single clergyman proves how Rome relies on the apostolic administrator as a tool to prevent vacancies in regions where vetting bishops remains stalled. Moreover, when looking at it, is impossible not to wonder if Africa is actually the miracle of intransigent “orthodoxy” the U.S. and Latin American Catholic far-right brag about every time they deride “Liberal” Catholics this side of the Atlantic.

For the time being, Rome rather goes with an “old hand” bypassing local priests in favor of a small circle of trusted, high-ranking prelates who can “hold” multiple jurisdictions simultaneously.

These African cases reveal that the migration to a new type of apostolic administrator is a global phenomenon. Whether it is Napier returning from retirement or Besungu managing three jurisdictions at once, these appointments show some caution with rushed promotions, while keeping also the institutional “black box” closed until a safe, long-term solution is identified.

Holding a crosier, Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo walks among cheering Catholics before Mass in Kinshasa, December 26, 2025. From the Kinshasa archdiocesan social media.

Geopolitical vs. internal crisis management

After the five years of hell in Palm Beach, and more so after Vos Estis Lux Mundi, apostolic administrators have been sent to jurisdictions with no state-imposed restrictions (e.g., the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Western Europe). This correlates, at least for the time being, with the difficulties the Catholic Church faces nowadays to appoint bishops with clean records.

One of the observed outcomes of the appointment of apostolic administrators have been the fusion of dioceses with “issues”. Despite its limitations, the dataset offers examples of how this has happened preceding the merger of dioceses.

One example comes from Canada. The data records the tenures of Jesuit Terrence Prendergast as administrator in Yarmouth and Alexandria-Cornwall, both were subsequently merged or joined with neighboring sees.

Another example comes from Alaska. The data follows a similar cycle where the archbishop Roger Schwietz served as administrator for neighboring sees, a pattern that preceded the Anchorage-Juneau merger.

Finally, the nature of the administrator as “temporary” appointment has changed. In the snapshots from the 1980s the administrator often served for months (e.g., Italian prelate Antonio Nuzzi in 1979, 9 months). In the 2020s, tenures frequently exceed two years (e.g., Rogelio Cabrera López in Nuevo Laredo, 26 months).

There is more data mining ahead to offer more precise conclusions, but already the available data show patterns that should give pause to whoever keeps betting on denialism as a solution for the global clergy sexual abuse crisis.

Despite its limits, the database allows to better understand what is happening now in the Catholic Church. As the story published on December 29, 2025, proves, there is a backlog in the appointment of bishops, and a challenge to fill 400 posts in the near future.

Also, as the story published on January 5, 2026, proved there is a thin bench, a weak farm system, running the risk of betting on the difficulties young males in the Global South have to access education or the labor market to recruit candidates to the priesthood.

Today’s piece offers a cautionary tale. It acknowledges the need to be cautious, to avoid fiascos such as the five years of hell in Palm Beach, Florida. In that regard the caution with which Rome uses nowadays the apostolic administrator appointment as a tool is a positive sign as it proves talks about a more cautious approach.

The risk, however, is that caution turns into a stalled system, one dismissing the need dioceses have of bishops able to lead their processes such as the Synod of synodality.

Pastors, deans and other prelates, can lead some aspects of the process, but it would be naïve to dismiss the need for a bishop able to decide. At the same time, makes no sense to rush appointments, if the appointments are risky as some of the cases cited in this piece have proved.

As good as it is to have tested bishops and cardinals addressing as apostolic administrators the needs of dioceses facing some kind of distress, one has to wonder if it is realistic to expect that archbishops about to reach 75 or already way over that mark, such as Rogelio Cabrera in Mexico or Napier in South Africa, are the best choices to lead these processes.

Next week there will be additional data and conclusions coming out of that evidence.

* * *

A summary of this piece is available as audio after this paragraph.

Note on production: The text of this summary was written and edited solely by the author. The delivery of the audio summary was achieved using a high-quality, text-to-speech engine Microsoft Word for Web. The AI was used for voice generation only, not content creation.